The king of Las Vegas is spinning the wheel in Europe

The words of Terry Benedict, fictional owner of the Bellagio casino in the 2001 Hollywood blockbuster Ocean’s Eleven, are ringing in my ears: “Congratulations, you’re a dead man.”

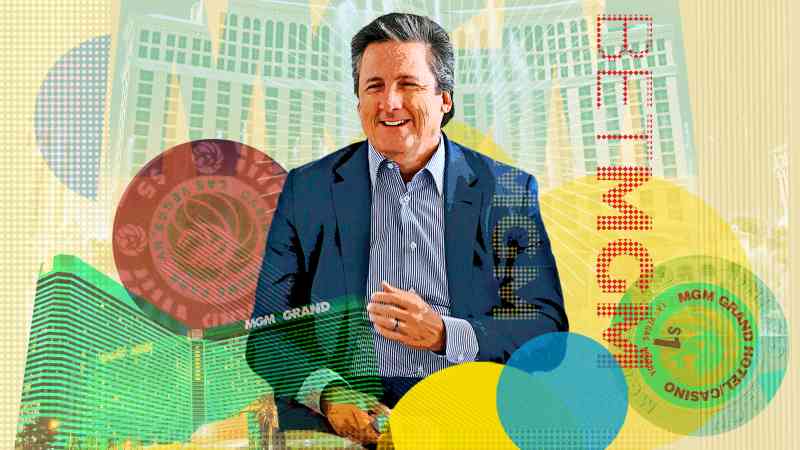

Benedict, played by Andy Garcia, has just learnt from the Brad Pitt character Rusty Ryan that the entire contents of the vault in his Las Vegas gambling emporium have been robbed. Why am I thinking about this? Because I’ve just asked Bill Hornbuckle, the real-life Terry Benedict, about the presence of the mafia on the Las Vegas strip.

There is a pause as the chief executive and president of MGM Resorts International arches an eyebrow and gives a withering sideways look. “Go back to 1977, you still had vestiges,” he sighs eventually. “Seven of the places had teamster money in them. But we know they are long gone now.”

It is hard not to think about the Ocean’s Eleven gangsters while sitting in Hornbuckle’s office. After all, it not only looks uncannily like his fictional version’s lair in the movie … it actually is. MGM gave director Steven Soderbergh access to shoot his movie all over its Bellagio flagship. With its marble floors, meeting rooms and antechambers clad with highly polished designer furniture, it feels more like a $100,000-a night penthouse suite than the executive offices of a blue-chip corporation.

But then this is Las Vegas, city of excess.

Probably the best-known operator on the Strip — owning fabled casinos such as the Grand, Mandalay Bay and Luxor — MGM is also the biggest casino operator in the world. The business traces its roots back to investor Kirk Kerkorian’s time as a major shareholder in the Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer movie studio. Kerkorian figured that the famous studio’s name could add glamour and swag to a Vegas hotel, and he used the brand to build a host of casinos around the world, starting with the Las Vegas MGM Grand Hotel and Casino in 1973.

Pretty soon, the casinos were making more money than the movie studios, and in the 1980s the resorts business was split off as a standalone business, doing battle with the billionaire Vegas tycoons Sheldon Adelson, Steve Wynn and, later, Donald Trump.

Spin the wheel forward to today and MGM Resorts International, valued at $12 billion (£9 billion) on the New York Stock Exchange, is the clear king of Sin City — but it faces a turf war on another front. Since the 2018 reversal of America’s decades-long ban on sports betting, online gambling has become the business where it’s all to play for.

Hornbuckle first came to Las Vegas 47 years ago to be a busboy at the luxurious Jockey Club suites that sit between the Bellagio and the city centre. He smiles fondly as he recalls looking after the whims of high rollers and fabled card-counters — people such as Ken Uston, who was so successful that he had to disguise himself to be allowed to play.

Vegas was a different place in those days — the city’s population totalled little more than 350,000; nowadays, it is almost three million — but gambling remains as popular as ever. At 8.30am in the Bellagio, scores of customers sit at row upon row of brightly coloured slot machines, and there are plenty of weary-eyed punters crowding the craps and blackjack tables.

The city’s reputation as a place for fun is increasingly being matched by its role as a venue for business conferences. Last week alone, Caesars Palace was hosting plasterers and cement-makers, the Mandalay Bay was full of zookeepers and the The Venetian Resort’s expo centre was the venue of choice for the discount fashion trade. “Where else in the world can you expect to get 100,000 new visitors every three days?” Hornbuckle asks.

The biggest bet among the Strip’s stalwarts, however, is on using their brands to persuade people to bet online. And in 2018, to learn how to play in this new game, MGM teamed up with the London-listed Ladbrokes-to-Coral betting group GVC, now called Entain.

“We needed to get paired up with somebody who really knew technology at scale and who could help us hit the ground running,” says Hornbuckle. “Five years later, we’ve got a $2.5 billion business and we are still growing the top line.”

The problem is that this American joint venture, called BetMGM, has been outflanked by rival tech-savvy bookmakers DraftKings and FanDuel — a subsidiary of Britain’s takeover-hungry Flutter, owner of Paddy Power and Sky Bet. BetMGM only has about 11 per cent of the US online sports betting market, which is a rapidly growing sector now that 30 states have legalised it. FanDuel and DraftKings have 35 and 32 per cent respectively, according to the market research firm Eilers & Krejcik Gaming.

“It’s not without its challenges, but we’re happy where we are,” is how Hornbuckle summarises all this in the New England twang that has survived nearly five decades in the desert. “I think the next year will be extremely telling.”

So excited was it by the prospects for US online gambling that, at the tail-end of 2020, MGM began talks to buy Entain outright for £8 billion. But in the January, MGM suddenly walked away. Ever since, the industry gossip has been that MGM will make another bid.

Hornbuckle ruled this out when asked in February 2023. “The simple answer is ‘no’, we’ve moved on,” he told investors. Now he seems more equivocal: “It’s the obvious question. I am just not going to comment on it.”

On the one hand, few would be surprised if he made a move. Entain is in a dismal negotiating position: its chief executive quit abruptly in December; its share price has halved in the past year, leaving the group worth less than £4 billion; and investment bankers from Moelis are conducting a strategic review of the company.

But on the other, why would he? Hornbuckle has made MGM far less dependent on its British partner since the abortive bid. He has been busy buying a host of companies this side of the Atlantic that not only give MGM new tech know-how, but also a European business that is now a force to be reckoned with. The biggest, in June, was the $3.75 billion deal to buy the German online bookmaker Tipico from private equity firm CVC.

In other words, while MGM is working with Entain in the US, it is now working against it in Europe. Adverts for the European arm of BetMGM — solely owned by the US firm — are as prominent in London Bridge railway station as they are at Las Vegas’s Harry Reid International airport.

So: does MGM actually need Entain anymore? “Oh yeah, for the technology,” Hornbuckle responds, before tailing off. “Well, yes, for today,” he adds.

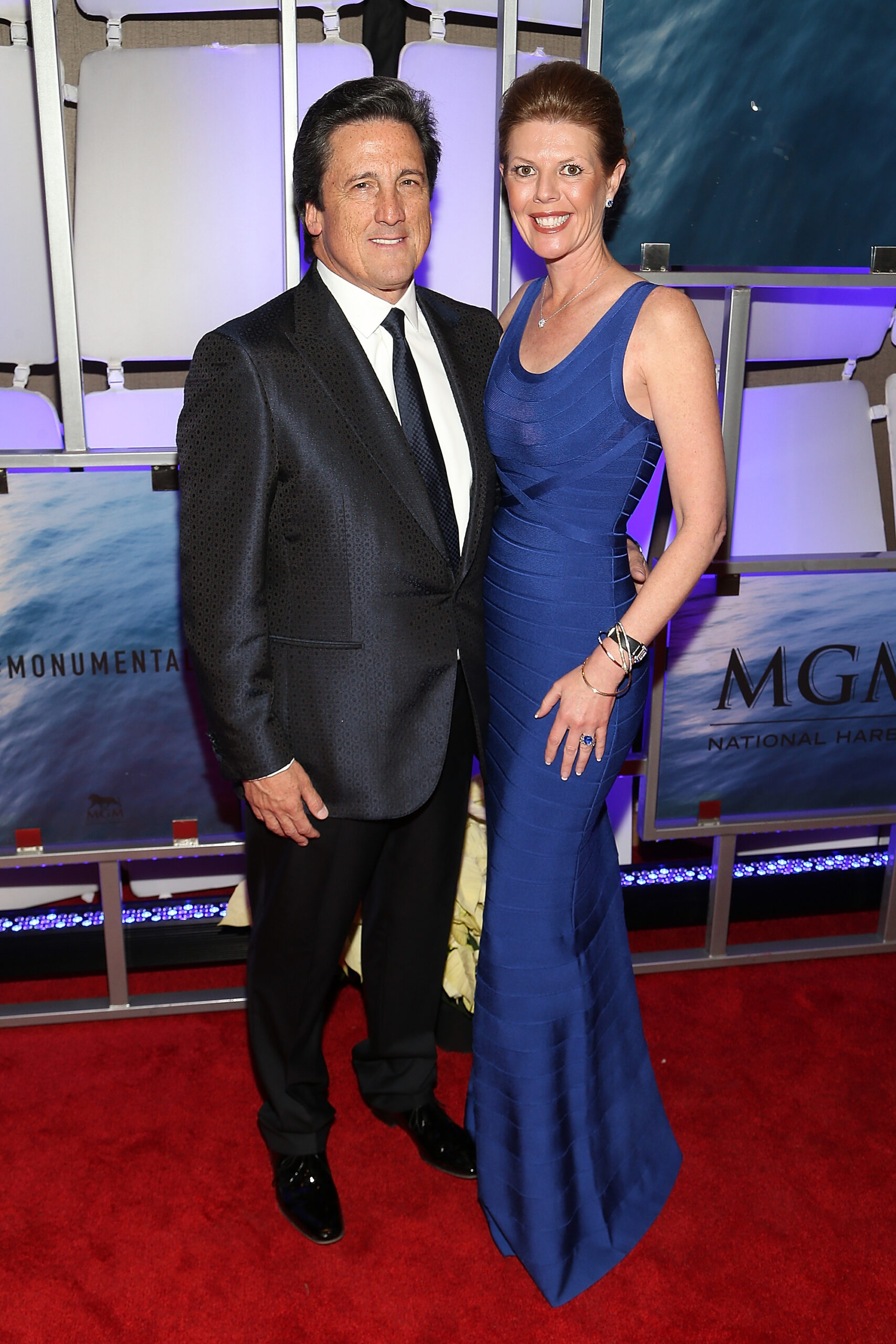

Dressed in a dark grey suit and open-necked white shirt, and with flecks of grey in his swept-back dark hair, Hornbuckle sips his coffee from a mug emblazoned with a “B” in regal font, denoting Bellagio.

He is Las Vegas corporate royalty. An American football sits in a glass case behind Hornbuckle with his name on it — a souvenir from when the National Football League’s Raiders team moved from Oakland, California, to Las Vegas in 2020. A shovel to commemorate when digging began on the team’s new $3 billion stadium leans against the wall under a 3ft-wide silver leaf statue of an eagle that sits behind his desk. “I like eagles,” he says. “They mean freedom.”

Hornbuckle explains that he has done “50 different jobs”, working his way up the corporate ladder since arriving in Vegas in the 1970s. Among these were running the Golden Nugget hotel and casino, where he had 65 cream pies slung at him for charity when the venue hosted the 1995 National Pie Championships.

In the 2000s, he spent a couple of years in the UK exploring how MGM could capitalise on Tony Blair’s plans to create a network of “super-casinos”, part of New Labour’s ideas for liberalising gambling.

During that time he came across Denise Coates, the reclusive billionaire founder of Bet365 who rarely meets industry counterparts, let alone makes public appearances. It has long been speculated that her business makes much of its fortune running online gambling sites in China — a country where betting is, in theory, illegal (Bet365 insists it operates legally).

“They run a great business. But look, they’re in markets we could never be in. Over history, they’ve done business in Asia that we could never touch.”

So China? “Yeah, full stop. We have a licence in Macau. That’s something we could not do.”

Hornbuckle may seem the all-American chief executive, but he was born on a US air force base in Japan and is married to a Brit, Wendy. They have just come back from holidaying with her family in Birmingham — a trip during which he was left less than impressed with Avanti’s perennially late-running trains.

He may insist that the mafia in Vegas are long gone, but MGM was attacked by criminals of the cyber variety last September. The hackers broke into its systems and demanded a $30 million ransom. Pandemonium ensued as everything from slot machines to hotel key cards stopped working. “It put us in an environment for about ten days that was very difficult.” It subsequently emerged that Vegas rival Caesars had been subject to a similar attack just days before. Caesars reportedly paid a $15 million ransom, contrary to FBI advice.

Hornbuckle took a tougher stance. “We refused to pay a ransom,” he says, proudly. “And we never closed. We got through it.”

Maybe there is just a tiny bit of Terry Benedict’s personality in him after all.

Post Comment